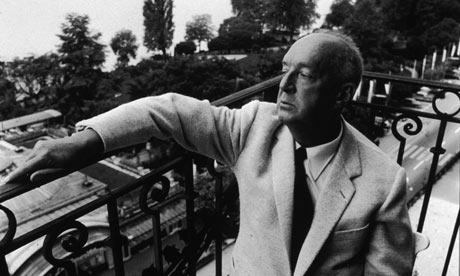

Vladimir Nabokov on the balcony of his suite at the Montreux Palace Hotel, Switzerland, 1965. Photograph: Getty Images

Vladimir Nabokov, the acclaimed author of Ada, Pnin, Pale Fire and that transgressive bestseller Lolita, is a writer whose imaginative mastery continues to torment successive generations. Behind the imminent publication of his posthumous 18th novel is an extraordinary story, a literary magician's spell.

On 5 December 1976, the New York Times Book Review published a pre-Christmas round-up in which a number of famous writers selected the "three books they most enjoyed this year". Vladimir Nabokov's response to this routine inquiry was at once moving and mysterious. Having revealed that he was seriously ill, he listed "the books I read during the summer months of 1976 while hospitalised in Lausanne": Dante's Inferno in the Charles Singleton translation, The Butterflies of North America by William H Howe (Nabokov was a world-famous lepidopterist) and, finally, The Original Of Laura. This, he wrote, was "the not-quite-finished manuscript of a novel which I had begun writing and reworking before my illness and which was completed in my mind".

With artful cunning, Nabokov proceeded to reveal a mystery that is only now, 33 years later, on the brink of being solved. "I must have gone through it [

The Original of Laura] some 50 times," he confided, "and in my diurnal delirium kept reading it aloud to a small dream audience in a walled garden."

Who could resist such entrancing fabrications ? "My audience," Nabokov went on, "consisted of peacocks, pigeons, my long dead parents, two cypresses, several young nurses crouching around, and a family doctor so old as to be almost invisible. Perhaps because of my stumblings and fits of coughing, the story of my poor Laura had less success with my listeners than it will have, I hope, with intelligent reviewers when properly published."

With that fleeting reference to "my poor Laura", the spell was almost wound up. There was just one more twist. Shortly after Christmas, provoked by that tantalising fragment in his newspaper, Herbert Mitgang, a

New York Times reporter specialising in books and writers, began to make inquiries of Nabokov's publisher and confirmed, as he reported on 5 January, that the celebrated author of

Lolita had indeed "completed his next novel in his head". This news he corroborated with Nabokov's New York editor, who told him: "It's all there: the characters, the scenes, the details. He [Nabokov] is about to do the actual writing on three-by-five-inch cards."

Writing on index cards, in pencil, had become Nabokov's preferred method of composition. He would fill each card with narrative and dialogue, shuffle the completed pack and then, in the words of his editor, "deal himself a novel". What literary news could be more thrilling? In summary, we now know that the novel concerns beautiful and promiscuous Flora Lanskaya, "the original of Laura", and her unhappy marriage to the grossly fat Philip Wild. The theme of the book, central to Nabokov, is Death and what lies beyond it. Wild is engaged on a process of self-dissolution, thinking away his corporeal self in a bizarre act of cerebral suicide. Next month we shall at last discover what this fabled manuscript actually amounts to; at the time there was only gossip.

Mitgang reported that the working title of this new novel by a contemporary European master was "Tool". This was, he speculated, "presumably an anagram, somehow based on a character named Laura". Fired by the mystery of "Tool", and the excitement of the quest, Mitgang flew to Switzerland. The 77-year-old Nabokov and his devoted wife, Vera, had lived there, amid the marble and chandeliers of the Montreux Palace Hotel, for more than 15 years.

Mitgang was to be slightly frustrated. The celebrated author refused to grant the

New York Times an interview, but he was, apparently, happy to entertain a purely social visit from Mitgang, who told the

Observer last week that he'd had "about half an hour in the hotel lobby with Nabokov". Mitgang says he found Nabokov to be "very cordial", but that he got little else from the meeting. He later wrote that it would be "idle to speculate about the title or the meaning [of 'Tool'] because Mr Nabokov likes to play games with words, ideas, and publishers". The true nature of the new book would not be vouchsafed "until those shuffled cards are typed into a manuscript".

None the less, having made the pilgrimage to Montreux, Mitgang was not going to go away empty handed. "And what," he asked, breathlessly breaking the rules of the encounter, "is the new novel about?"

"If I told you," Nabokov demurred, with teasing courtesy, "that would be an interview." Never had the magician cast a better spell. He had done it often enough before, in print. As he said in his memoir,

Speak, Memory: "I like to fold my magic carpet, after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon another." This time illusion and reality would become tragically fused.

For Nabokov, art and life were always "a game of intricate enchantment and deception". Lolita, his most famous creation, is an enchantress. His greatest novels display extraordinary narrative legerdemain and fiendish invention, partly inspired by the ludic interaction of English and Russian. Of himself, he wrote that, in his imagination: "I appear as an idol, a wizard, bird-headed, emerald-gloved, dressed in tights made of bright-blue scales."

Perhaps you have to be an aristocrat born on Shakespeare's birthday to play Prospero. Nabokov came from a family of almost impossible grandeur, Russian liberals who fled the Crimea in 1919. As a young man, after a Cambridge education, he stumbled into a career as a drifter, a collector of butterflies and author of strange books. A brilliant outsider, he established a modest literary reputation across the Europe of the 1920s and 1930s, supporting himself through lessons in English and tennis and crossword puzzles composed for a Russian emigre newspaper.

In 1940, fleeing the Nazis, Nabokov embarked on a second exile to America, landing in New York with just $100. Here, in his early 40s, he started to write in English for the first time. His young cousin, the renowned French publisher Ivan Nabokov, says: "Vladimir had an English nanny. English was his first language and he always had a terrific ear."

Nabokov eventually found his niche, teaching at Wellesley College and Cornell and finally publishing

Lolita, after many rejections, in 1955. After years of living in a kind of literary twilight, the sensational success of that great literary narcissist, Humbert Humbert, and his scandalous predilection for "light of my life" Dolores Haze, thrust Nabokov under the hot lights of American celebrity. It was not a congenial experience and in 1961 he retired to Switzerland with his wife to devote himself to his books.

Now the plot thickens again. The first major novel to spring from his pencil after

Lolita spookily rehearses the strange afterlife of "Tool"

. Pale Fire (1962) has been described, by Mary McCarthy, as "a jack in the box, a Fabergé gem, a clockwork toy, a chess problem, an infernal machine".

John Shade, a famous American poet, murdered in 1959, has left a final poem. Nabokov gives the reader four cantos of

Pale Fire, 999 lines of rhyming couplets, plus an editor's foreword and scholarly annotations. When the disparate parts of the manuscript are fitted together, a novel of many planes and levels is revealed, a novel inspired by games of chess, the heroic couplets of Alexander Pope and the lambent mysteries of nature (

Pale Fire is full of lakes, trees and butterflies).

And the poem? This, we are informed by Charles Kinbote, the editor of Shade's posthumous masterpiece, "consists of 80 medium-sized index cards" on which the poet, Shade, has written out "in a minute, tidy, remarkably clear hand, the text of his poem..." Already,

The Original Of Laura has its antecedents.

But not yet a title. When "Tool" first surfaced in Nabokov's notebooks, in 1974, it was

Dying Is Fun and then

The Opposite of Laura. If Nabokov hoped he could tease his worldwide readership, some of whom loved him close to idolatry, with

The Original of Laura as work in progress, he was to be cruelly denied. Mitgang says that when he met the novelist in the new year of 1977, "he seemed to be old, but in good health". In fact, Nabokov was dying. When the BBC filmed him in the spring of 1977, he was low in the water and visibly sinking. He moved slowly, his skin was "grey and flabby" and he was breathing hard.

As his condition deteriorated, he worked obsessively to finish the new novel that was so synaesthetically vivid in his imagination. In the end, he had to acknowledge his fate. If the manuscript could never be finished to its perfectionist author's satisfaction, it must never see the light of day. Now the spell he had nurtured would become an old man's malediction. He instructed Vera that, after his death, it should be destroyed forthwith.

Nabokov died from bronchitis on 2 July 1977, in the presence of his family and, according to his son, Dmitri, "with a triple moan of descending pitch". The writer's departure seems like just another piece of wizardry. "The echo is so strong," his son writes, "that I imagine that it is indeed all staged, that he will soon speak again."

It could not be and the spell became a curse. The 138 index cards of "Tool

" were placed in a safe deposit box in the vault of a Swiss bank while Vera wrestled with her late husband's injunction. From time to time, she enlisted sympathetic outsiders for advice. Brian Boyd, Nabokov's distinguished biographer, was given a taste of the manuscript amid conditions of great secrecy during the mid-80s and advised against publication, an opinion he later rescinded. "People shouldn't expect to be swept away," he has said, tactfully. "It's the kind of writing that induces admiration and awe but not engagement."

Those for whom Nabokov is, in the words of Martin Amis, "the laureate of cruelty", see his deathbed decree as peculiarly vexing. But it was not unique. Virgil instructed his heirs to destroy The Aeneid, and was defied by the emperor Augustus. Kafka asked his friend Max Brod to burn all his papers, which included the novels we know as The Trial and The Castle. "Fortunately," said Nabokov in his own lecture on Kafka, "Brod did not comply with his friend's wishes." This remark has been used by the Nabokov estate as a prescient approval of its failure to destroy The Original of Laura.

The burden of administering the Nabokov estate had fallen to the writer's beloved son, "my dearest Dmitri", who was also known to his father as Mitya, Mityusha, Mityenka, Mityushenka and Dmitrichko. An only child, Dmitri has always expressed a quasi-tribal loyalty to the Nabokov name, but that is not the whole story. Vladimir loathed music and never learned to drive; Dmitri is a one-time opera singer with a love of fast cars. In the narrative of what happened next, the complexity of the father-son relationship has played a vital part. Last week, his cousin Ivan Nabokov described to the

Observer the executor's anguish. He remembers Dmitri telephoning for support. "If you're asking me, I replied, you've already made up your mind: your instruction was to destroy it. ."

Now 75, Dmitri, known to the Italian press as "Lolito", is as tough, vivid and entertaining, fast-talking and Americanised as his father was elusive, sweet-natured and immemorially Russian. For years, he lived in the Nabokov apartment in Montreux, or in Palm Beach, enjoying a playboy lifestyle with Ferraris and a string of girlfriends. In his time, he has been a passionate mountaineer and a racing driver until a near-fatal crash in 1980 curtailed all climbing, singing and driving.

When Vera Nabokov died in 1991, there was no escaping the family curse. Dmitri, who had already made an admired translation of Nabokov's ur-Lolita,

The Enchanter, welcomed an immersion in his father's work as a way of remaining close to him. "When the task passed to me," he writes in his introduction to

The Original of Laura, it was as though he "had never died, but lived on, looking over my shoulder in a kind of virtual limbo, available to offer a thought or counsel to assist me with a vital decision".

It is not known when Dmitri first began to study the 138 index cards, but when he did he seemed to make up his mind.

The Original of Laura, he wrote, was "the most controlled distillation of my father's creativity, his most brilliant novel". Nevertheless, he continued to vacillate, like Hamlet, in the execution of his filial obligation to his late father's request. Once again, he turned to his publisher-cousin.

About 10 years ago, the index cards of "Tool" were converted into a 76-page typescript and shown to Ivan Nabokov and some others in the estate's inner circle. Nabokov says, pointedly, that, "We were all of the same opinion. It was just a torso, and not a glorious torso." But now, once again, life was intruding on art. Entering his 70s, Dmitri Nabokov

was progressively unwell with a grim tally of geriatric afflictions involving expensive Swiss doctors. To put it bluntly, he needed the money. Then, in 2005, there was a new twist.

Ron Rosenbaum is a New York journalist who happens to believe, as he told the Observer, that Vladimir Nabokov is "the greatest writer of the 20th century, the only one close to William Shakespeare's level". In November 2005, Rosenbaum, who enjoys a reputation as a literary gadfly, wrote a column, "Dear Dmitri, Don't burn Laura!" in the New York Observer.

Having rehearsed the history of "Tool", Rosenbaum reported an email exchange with Dmitri Nabokov

about the manuscript ("He will probably destroy it before he dies!") and closed with a passionate plea: "Won't some university library step forward with a detailed plan for funding the preservation of

The Original of Laura, this irreplaceable literary treasure ?"

The result: uproar. The eccentric, worldwide fraternity of Nabokov scholars had a field day. Dmitri, apparently maddened by the controversy, now adopted his father's teasing stance. He declared himself to be "torn" between his obligations to posterity and to his father's shade. Asked if he would burn or shred the manuscript, he replied, mischievously: "Perhaps I already have and prefer not to reveal the method."

The teasing went both ways. In 1991, an American librarian published a literary critical essay, apparently by a Swiss professor, entitled "A first look at Nabokov's last novel", which was quickly exposed as a brilliant spoof. Others became entangled in the debate. "It's perfectly straightforward," said Tom Stoppard. "Nabokov wanted it burnt, so burn it."

Novelist Edmund White, whose early work had been championed by Nabokov, was equally blunt. "If a writer really wants something destroyed," he told the Times, "he burns it." John Banville said that this situation was "a difficult and painful one". Conceding that The Original of Laura may turn out to be inferior, Banville decided that it should be saved from the flames. "A great writer is always worth reading," he said, "even at his worst."

So how good was

The Original of Laura, and what was its place in the Nabokov canon? Ron Rosenbaum, who had begun to exhibit some of the symptoms that afflict everyone who approaches this manuscript, was now on a mission to find out and it left him wanting, he said, "to spend the rest of my life trying to evaluate its relationship to the rest of VN's work". But when he spoke to the

Observer recently, Rosenbaum admitted that he was "deeply conflicted" about what he had seen.

Ivan Nabokov, who has watched this saga from the privileged position of one who actually knew the author, can't quite see what the fuss is about. "To me, it's an inconsequential matter," he told the

Observer, but as a distinguished former editor he fully understands the publishers' dilemma. Never mind the "burn or not to burn" question; here is a highly publicised, highly prized volume that's barely 76 pages long, by an author who wanted it destroyed, for which several imprints worldwide have paid a lot of money.

"Sonny Mehta at Knopf has come up with a brilliant solution," he says. Designed by Chip Kidd,

The Original of Laura will appear in a highly collectible edition: Nabokov's handwritten index cards are reproduced in facsimile to display his neat handwriting, his furious crossings-out and his fascinating inserts. There's one valedictory wink from the great magician, a final card containing a list of synonyms for "efface" – expunge, erase, delete, rub out, wipe out and... obliterate.

Better late… Other posthumous novels

CG Jung (d.1961)

The Red Book Begun after falling out with Sigmund Freud in 1913, this 205-page book with 212 illustrations detail what appears to have been a psychotic episode in Jung's life. A Jungian scholar finally persuaded the family to publish the book this month, nearly half a century after it was written.

Kurt Vonnegut (d.2007) Look at the Birdie: Unpublished Short Fiction This collection of 14 short stories includes one about insect-sized people and one about an evil machine that tells listeners what they want to hear. A second collection is scheduled for autumn 2010.

William Styron (d.2006) The Suicide Run: Five Tales of the Marine Corps To be published next year is a book of five tales loosely based on Stryon's experience in the US Marine Corps. They include the first chapter of an unfinished novel and a previously unpublished short story.

David Foster Wallace (d.2008) The Pale King Also published next year, but already extracted in Harpers and the New Yorker, this is Foster Wallace's unfinished novel about the "intense tediousness" of working for the Internal Revenue Service.