Dieter Eduard Zimmer, essayist, editor, translator, an intellectually “incorruptible” “Renaissance man” (I quote from the German Wikipedia) and among much else Nabokov’s most important translator, editor, and longest-serving scholar, has died in Berlin on June 19, 2020, aged 85.

Born in Berlin in 1934, where he remained through and after the war, Dieter in 1950 was awarded an AFS scholarship to study for a high-school year in Evanston, Illinois. He studied literature and linguistics in the Free University of Berlin, and in Evanston again, at Northwestern University, under Joyce scholar Richard Ellmann, who became a friend. He worked briefly as a language tutor in Geneva and France. In 1958 he read a Time magazine review of Lolita and decided this was the kind of book for him. He wrote to Rowohlt Verlag, although he knew no one there, suggesting they acquire the rights; they already had, even before Hurricane Lolita had swept America. Returning to Germany, he became in 1959 a staff writer for Die Zeit, the Hamburg-based national weekly newspaper, something like a distillation of the best of The New York Times and The New York Review of Books. One of his first assignments was to write in October 1959 a review of the German Lolita. Nabokov told Heinrich Maria Ledig-Rowohlt, who would quickly become his closest friend among his publishers, that Zimmer’s review was, “seen internationally, the most intelligent review” he had encountered so far (Rowohlt to Véra Nabokov, 20 February 1960, VNA).

Dieter was asked to translate The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, and did, though he found this first exercise in translation (1960) difficult. Next came the far more difficult Bend Sinister (1962). Rowohlt reported to Véra, on the subject of translators: “Zimmer is really a trouvaille and an exception. He even went so far as to localize the lines of the poem taken from Melville/Moby Dick in BEND SINISTER and to solve the complicated riddles of the Shakespeare/Hamlet passages. I really think no translator I have ever known would have been able or intelligent enough to do that. It is really a pity that Zimmer is a literary editor in one of our leading weeklies so he is doing translations only as a side line job and only because he admires your husband’s work” (30 November 1960, VNA). Nevertheless the stringent, exacting feedback Véra Nabokov sent from her husband and herself on this and other translations showed Dieter the singular standards of accuracy and uncompromising precision the Nabokovs required, and he learned to meet them. Rowohlt asked him next to translate Speak, Memory (1964) and also to prepare a bibliography to keep track of Nabokov’s publications in their various modes, forms, and languages, not an easy task in German libraries still recovering from war damage. Véra Nabokov again supplied her meticulous corrections, and Rowohlt had the result published as an elegant slim brochure, a 1963 Christmas gift for his friends; a revised edition would appear in 1964. This became the basis for all subsequent Nabokov primary bibliography, although not for the errors Andrew Field introduced in his 1970 Nabokov: A Bibliography. Zimmer also translated some of Nabokov’s stories (in the volume Frühling in Fialta, 1966), and came to Montreux to interview Nabokov for German television, for Norddeutscher Rundfunk in 1966, and for Hessischer Rundfunk in 1974. He also translated into German James Joyce (Dubliners), Edward Gorey, Nathanael West (Miss Lonelyhearts), Ambrose Bierce, Jorge Luis Borges and others.

Meanwhile (always as Dieter E. Zimmer, to distinguish himself from Dieter Zimmer, a television journalist and novelist) he was becoming a leading figure in Die Zeit and more broadly in German literary and intellectual culture. By 1963 he had become the indispensable assistant of the editor of the feuilleton (features) section of the newspaper, until he was himself appointed editor of the feuilleton in 1973. In 1977 he became one of the four main editors of Die Zeit itself, and a columnist specializing in psychology, biology, medicine, linguistics, and information science. He retired from Die Zeit in 1999 to write full time.

During his years in Die Zeit he became known throughout the German-speaking world as an essayist, and for the books collecting his essays on particular themes, including his devastating attacks on psychoanalysis, Tiefenschwindel: Die endlose und die beendbare Psychoanalyse (Depth Swindle: Endless and Endable Psychoanalysis, 1986), which greatly amused Véra Nabokov; technology, especially information technology, including Die Bibliothek der Zukunft: Text und Schrift in den Zeiten des Internet (The Library of the Future: Text and Writing in the Age of the Internet, 2000); and language (German and language as a human capacity), on which he published at least five well-received books. He was renowned for his succinct, clear style that could make complicated subjects accessible. I recall mentioning his name to a German colleague in my university’s German Department, who was most impressed that I knew him: he told me he had long been thinking of editing an anthology of German-language essays, and certainly intended to include Zimmer, whom he rated one of the great post-war essayists in German.

Zimmer always had a hunger for facts and accuracy as well as his passion for Nabokov. These traits coalesced in his role as editor of the German Gesammelte Werke. Michael Naumann, the head of Rowohlt since 1986, and a friend and former Die Zeit colleague, proposed the collected works project to Rowohlt’s financiers, not expecting it to make money, although in fact it would do rather well. With an unrealistically hopeful plan of completing the set of twenty-four numbered volumes by 1995, the edition began in 1989 with Lolita (volume 8) and an unnumbered supplement, Marginalien, of writing by Nabokov and others (Bitov, Boyd, Updike, Zimmer). Although the Gesammelte Werke were not academic editions, and were beautifully if soberly presented to appeal to a wide readership, they went well beyond the needs of commerce. Translations were corrected or entirely redone by Zimmer, often with rich notes that he supplied—in the case of Ada, over 300 pages and, characteristically, many plates of images. He provided editorially thoughtful versions, including the material in Drugie berega absent from Conclusive Evidence/Speak, Memory, and in the case of the Lolita screenplay, the only publication of the complete Nabokov version in any language (volume 15:2, 15:1 being the drama). He added to Deutliche Worte (Limpid Words, 1993, the translation of Strong Opinions) a partial prefiguration of Think, Write, Speak, in Eigensinnige Ansichten (Stubborn Opinions, 2003). The intended Eugene Onegin translation and commentary did not materialize, within the Gesammelte Werke (although Stroemfeld did publish in 2009 Sabine Baumann's translation of EO from the Russian and Nabokov's commentary from the English, which together won a translation prize) but the set ended as planned, at number 24, with the unforeseen Briefe an Véra (2017).

With his interest in science and his expertise in Nabokov, Zimmer was the obvious person to approach for help in staging a 1993-94 exhibition of Nabokov’s European butterfly catches, which Véra Nabokov had gifted to the Musée cantonal de Lausanne. He did much more than the initially expected identification of butterfly passages in Nabokov’s work, preparing the 175-page Nabokov’s Lepidoptera: An Annotated Multilingual Checklist, included in and indeed taking up almost all of Michael Sartori, ed., Les Papillons de Nabokov (Lausanne: Musée cantonal de Zoologie, 1993). That checklist steadily and rapidly metamorphosed over the next decade into a privately printed, repeatedly updated, at first softbound then hardbound Guide to Nabokov’s Butterflies and Moths, which by its last printed edition reached 394 packed A4 pages and 21 color plates. (To those he knew would be interested, he would send each update, thinking it the last.) From then on Zimmer kept updating it on a section of his increasingly elaborate website. With its discussion of butterfly species and subspecies mentioned by Nabokov in his literary and his scientific works (full of cross-references to include popular names and changes in scientific taxa), a page-by-page record of the references to butterflies in the literary works, a detailed biographical index of lepidopterists of importance to Nabokov, an index of Nabokovian butterfly names, and illustrations of butterflies in life and art of importance to Nabokov, it is an incomparable resource for Nabokovians with any interest in one of the writer’s two main passions. Typical of Zimmer’s precision and his generosity is his providing not only the Latin binomials for each species and subspecies, but also the English, French, German, Italian, Russian, and Spanish names, so that translators into the major European languages could be as responsible as he was. As I wrote in celebrating the 2001 edition, Nabokov “would have had to blink back or wipe away tears of gratitude” at the Zimmer Guide. By the time Stephen Blackwell and Kurt Johnson invited Dieter to contribute to their collection Fine Lines: Vladimir Nabokov’s Scientific Art (Yale, 2016), his health would be too poor for him to accept, but the volume is fittingly and elegantly dedicated to him: “To Dieter E. Zimmer, an inspiration to all who chase after Nabokov’s receding footsteps.”

Retired from Die Zeit and with most of the Gesammelte Werke published and the butterfly guide nearing its final avatar, Zimmer began researching other guides to Nabokov. First came Nabokovs Berlin (Berlin: Nicolai 2001), with an essay on Nabokov’s relation to Germany, a translation of “A Guide to Berlin,” and sumptuous, carefully researched picture essays on Nabokov’s 1910-11 and 1921-1937 sojourns in Germany, with revealing photographs often placed opposite generous quotations from his fiction and memoirs, and a chronicle and map.

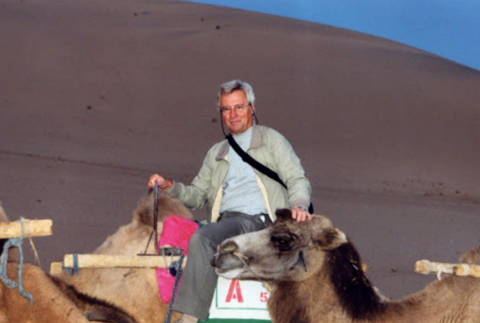

Next came Nabokov Reist im Traum in Das Innere Asiens (Nabokov Journeys by Dream into Central Asia, Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 2006). Again Zimmer is lushly comprehensive, reproducing Fyodor’s inset biography of his father, Count Konstantin Godunov-Cherdyntsev, and his dream-assimilation into his father’s expeditions of entomological discovery; then excerpts from Fyodor’s and Nabokov’s sources, including Mikhail Grum-Grzhmailo and Nikolay Przhevalsky, but also Marco Polo, Sir John Mandeville and more, illustrated with maps, photographs, and lithographs, and an essay on Nabokov’s use of “the amazing music of truth.”

Finally, at least in book form, came Wirbelsturm Lolita: Auskünfte zu einem epochalem Roman (Hurricane Lolita: Information on an Epoch-making Novel, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 2008), with essays on Lolita as scandal, on precursor cases like Sally Horner’s or names like Lillita Chaplin, on the celebrated but elusive ape drawing the bars of its cage, on Michael Maar’s claim that Nabokov drew unconsciously on Heinz von Lichburg’s 1916 story “Lolita,” on Lolita as road novel, on Lolita covers and more, with a calendar and a thick sheaf of reproductions of contemporary postcards. Auskünfte, “information” is a natural approach for Zimmer: he is a positivist, interested in specific fact rather than airy interpretation. Much though he loved Nabokov, he left Nabokov’s metaphysics to others.

Although, sadly, none of these books found a publisher outside Germany, Dieter used his website to make much of their contents available in English, often in updated versions (now 200 covers of Lolita editions), along with entirely new material, such as an elaborate family tree of the Nabokovs, much more comprehensive than anything Nabokov’s cousin, the impassioned family genealogist Sergey Nabokov was able to assemble; an essay researching the ghastly death of Nabokov’s brother Sergey; another on Nabokov’s limited competence in German; a richly illustrated chronology and gazetteer of Nabokov’s whereabouts with maps, photographs, postcards, and satellite images; and still more.

German was not one of Nabokov’s main languages, and in Germany in the decade when Nabokov was coming to worldwide attention “the spirit of cultural revolution that came out of the student rebellion of 1968” made authors such as him “vieux jeu at best—or representatives of a despicable outdated culture that everybody was called upon to combat” (Zimmer 1994). Despite a few German PhDs on Nabokov, published as books, in the North European way, there was no deep body of German scholarship on Nabokov, “not a single professor in the three German-speaking countries,” Zimmer could write in 1994, “who has come forth with a scholarly work on Nabokov and who would come to mind as a Nabokov authority” (Zimmer 1994), and no lively and collegial Nabokov community, as was beginning to emerge in Nabokov studies in North America, England, France, Russia, and Japan. That may in part be because Dieter Zimmer, a one-man promoter and enabler of Nabokov within Germany, stood outside national and international academic networks. Yet the Germans who turned in growing numbers to reading Nabokov knew of his authority and his contribution. The Polish-German writer Marcel Reich-Ranicki (1920-2013), perhaps the most influential German literary critic of his time, wrote of Zimmer in 1995: “What he has achieved as a translator, editor and bibliographer in this regard is so enormous and so exceptional that it may seem presumptuous to lavish on his work the usual sentences of praise. But we owe him more than most German poets and novelists of our day. Why do we have the many literary prizes that are so gladly bestowed on those who have already won ten awards?”

Dieter contacted me in 1987 as I was reaching the late stages of the Nabokov biography and as he was trying to work out whether there were uncollected or unpublished Nabokov stories that should go into the Gesammelte Werke story volumes. I had been meaning to interview him for years, but had undertaken my Berlin footslogging years before and had no opportunity to return there. But by letters printed on dot-matrix printers (mine missing quite a few pins, I notice now) we were soon asking and receiving much from one another, in my case especially information about German realia (I had stumbled on the right source!). In 1989 he asked me to contribute to his Marginalien volume, and I asked him to read and check the printout of Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, the only person I asked to do so outside the US (except of course for Véra Nabokov, who had been reading the chapters as they were written).

Although Dieter had announced the Gesammelte Werke in the Nabokovian in the fall of 1991 (Number 27, p. 10), he joined the Nabokov community at large especially through the listserv Nabokv-L, founded in 1993 by Don Barton Johnson. Don was very appreciative and welcoming in introducing Dieter to other Nabokov scholars and enthusiasts on 13 September 1994: “Dieter Zimmer, the author of the following remarks, is the Editor of the Collected Works of Nabokov in German, a truly stunning enterprise that offers much of interest to English-speaking Nabokovians with its copious annotations that add substantially to an understanding of many of the works.” Dieter’s essay (cited above as “Zimmer 1994”) on the Rowohlt edition and on his own trajectory as a Nabokovian—up to that point at least, for he still had so much to contribute—supplied me with much of what I have been able to say here, but has a charm all his own. Thereafter Dieter contributed regularly to Nabokv-L when it really was a daily means of immediate exchange for Nabokov scholars, students, and passionate readers. He appeared at some Nabokov conferences, not many (or did I just miss being at some of the same ones?), at Cambridge in 1999, at the Nabokov Museum in 2002, and I think at one of the conferences in Nice?

As can be seen from his marshalling facts and images for readers in his Nabokov editions, books, and website resources, or by trawling through his contributions to Nabokv-L available now on thenabokovian.org, Dieter was singularly generous as a scholar and as preserver of Nabokov’s legacy. In the 2000s, conscious, through all his research and writing on information technology, of the limited longevity and accessibility of digital data, he sent out to leading Nabokov repositories and to leading scholars large folders and CD collections of Nabokov print and television interviews, documentaries, and films.

Despite his high achievements as a Nabokovian and as a German writer, editor, and public intellectual, Dieter remained in person modest, even diffident, shy, reserved: he wrote to Nabokov of “a certain natural inhibition” (24 January 1962, VNA). He might seek out a table by himself at a writers’ and readers’ function, until others sought him out; or it might remain uncertain until the last minute whether he would even turn up to a banquet where he was all but the guest of honor. He made it difficult to tell him how much he was admired for his integrity, his intelligence and discernment, his unflagging curiosity, meticulousness, tenacity, energy, and thoughtful generosity.

He will be missed, he will be remembered and treasured, and his work will live on.

He is survived by his wife and occasional co-author, Sabine Hartmann, who will maintain his website.

Brian Boyd

Comments2

Djinn

DZ's essay "Chinese Rhubarbs and Caterpillars" (re: Father Dejean and Tatsienlu) is one of the most exciting and precise pieces of VN's scholarship I've ever known, I'll just post a link here.

immer, immer

Where the woods get ever dimmer,

Where the Phantom Orchids glimmer —

Esmeralda, Dieter Zimmer.